Conditions Explained

Disclaimer:

This website is intended to assist with patient education and should not be used as a diagnostic, treatment or prescription service, forum or platform. Always consult your own healthcare practitioner for a more personalised and detailed opinion

Sleep Apnoea

We have selected the following expert medical opinion based on its clarity, reliability and accuracy. Credits: Sourced from the website Patient Uk, authored by Dr Louise Newson (see below). Please refer to your own medical practitioner for a final perspective, assessment or evaluation.

Overview

There are two types of sleep apnoea: obstructive and central. Obstructive sleep apnoea is the more common of the two.

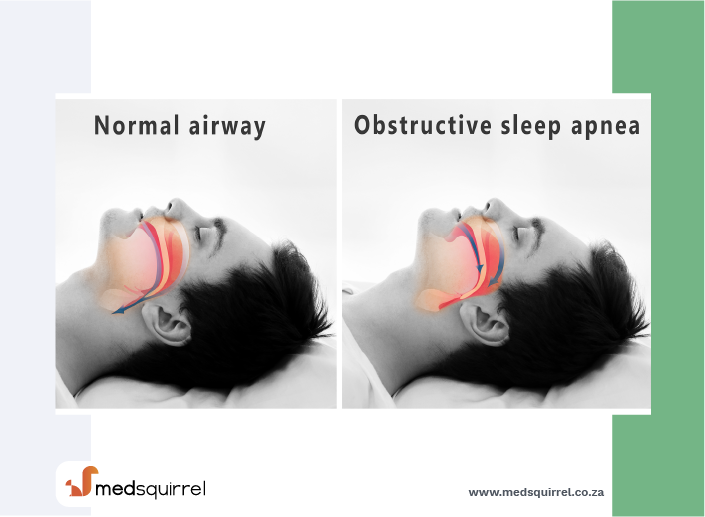

Obstructive sleep apnoea occurs as repetitive episodes of complete or partial upper airway blockage during sleep. During an apnoeic episode, the diaphragm and chest muscles work harder as the pressure increases to open the airway. Breathing usually resumes with a loud gasp or body jerk. These episodes can interfere with sound sleep, reduce the flow of oxygen to vital organs, and cause heart rhythm irregularities.

In central sleep apnoea, the airway is not blocked but the brain fails to signal the muscles to breathe due to instability in the respiratory control centre. Central apnoea is named as such because it is related to the function of the central nervous system.

Onbstructive sleep apnoea syndrome

What is obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS)?

OSAS is a condition where your breathing stops for short spells when you are asleep. The word apnoea means without breath - that is, the breathing stops. In the case of OSAS, the breathing stops because of an obstruction to the flow of air down your airway. The obstruction to the airflow occurs in the throat at the top of the airway.

You may also have episodes where your breathing becomes abnormally slow and shallow. This is called hypopnoea. Because there can also be these episodes of hypopnoea, doctors sometimes use the term 'obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome'.

What happens in people with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS)?

When we sleep, the throat muscles relax and become floppy (like other muscles). In most people, this does not affect breathing. If you have OSAS, your throat muscles become so relaxed and floppy during sleep that they cause a narrowing or even a complete blockage of your airway.

When your airway is narrowed, and the airflow is restricted, at first this causes snoring. If there is a complete blockage then your breathing actually stops (apnoea) for around 10 seconds. Your blood oxygen level then goes down and this is detected by your brain. Your brain then tells you to wake up and you make an extra effort to breathe. Then, you start to breathe again with a few deep breaths. You will normally go back off to sleep again quickly and will not even be aware that you have woken up.

Sometimes, the airway can just partially collapse and can lead to hypopnoea. Breathing becomes abnormally slow and shallow. If this happens, the amount of oxygen that is taken into your body can be halved. Hypopnoea episodes also usually last for around 10 seconds.

If someone watches you, he or she will notice that you stop breathing for a short time and then make a loud snore and a snort. You might even sound as if you are briefly choking, briefly wake up and then get straight back off to sleep.

It is quite common for many of us to have the odd episode of apnoea when we are asleep, often finishing with a snort. This is of no concern. In fact, some people when they sleep have periods of 10-20 seconds when they do not breathe. However, people with OSAS have many such episodes during the night. For the diagnosis of OSAS, you need to have at least five episodes of apnoea, hypopnoea, or both events per hour of sleep. However, there are different levels of severity of OSAS (mild, moderate or severe). People with severe OSAS can have hundreds of episodes of apnoea each night.

OSAS is usually classified as:

- Mild OSAS - between 5-14 episodes an hour.

- Moderate OSAS - between 15-30 episodes an hour.

- Severe OSAS - more than 30 episodes an hour.

So, if you have OSAS, you wake up many times during the night. You will not remember most of these times, but your sleep will have been greatly disturbed. As a consequence, you will usually feel sleepy during the day. Daytime sleepiness in someone who is a loud snorer at night is the classic hallmark of someone who has OSAS.

Who gets obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS)?

OSAS can occur at any age, including in children. It most commonly develops in middle-aged men who are overweight or obese, although it can affect people who are not overweight. It is thought that as many as 4 in 100 middle-aged men and 2 in 100 middle-aged women develop OSAS.

Factors that increase the risk of developing OSAS or can make it worse include the following. They all increase the tendency of the narrowing in the throat at night to be worse than normal:

- Overweight and obesity, particularly if you have a thick neck, as the extra fat in the neck can squash your airway.

- Drinking alcohol in the evening. Alcohol relaxes muscles more than usual and makes the brain less responsive to an apnoea episode. This may lead to more severe apnoea episodes in people who may otherwise have mild OSAS.

- Enlarged tonsils.

- Taking sedative drugs such as sleeping tablets or tranquilisers.

- Sleeping on your back rather than on your side.

- Having a small or receding lower jaw (a jaw that is set back further than normal).

- Smoking.

You may also have a family history of OSAS.

What are the symptoms of obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS)?

People with OSAS may not be aware that they have this problem, as they do not usually remember the waking times at night. It is often a sleeping partner or a parent of a child with OSAS that is concerned about the loud snoring and the recurring episodes of apnoea that they notice.

One or more of the following also commonly occur:

- Daytime sleepiness: This is often different to just being tired. People with severe OSAS may fall asleep during the day, with serious consequences. For example, when driving, especially on long monotonous journeys such as on a motorway. A particular concern is the increased frequency of car crashes involving drivers with OSAS. Drivers with OSAS have a 7-12 increased risk of having a car crash compared to average. You should not drive or operate machinery if you feel sleepy.

- Poor concentration and mental functioning during the day. This can lead to problems at work.

- Not feeling refreshed on waking.

- Morning headaches.

- Depression.

- Being irritable during the day.

Some people with OSAS find that they get up to pass urine frequently during the night. Less common symptoms also include night sweats and reduced sex drive.

People with untreated OSAS also have an increased risk of developing high blood pressure. Having high blood pressure can increase your risk of having a heart attack or stroke. People with untreated OSAS may also have an increased risk of developing problems with blood sugar regulation and type 2 diabetes.

How is obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS) diagnosed?

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

If you have daytime tiredness, sometimes a questionnaire is used to measure where you are on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. It is copyright protected, but your GP may have a copy for you. This helps to gauge the level of sleepiness that you feel during the daytime. A high score indicates that you may have a sleeping disorder such as OSAS.

Tests to confirm OSAS

If you have symptoms that suggest OSAS, or a high score on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, your GP may refer you to a specialist for tests. There are various types of test that can be done whilst you sleep.

The ones done may be determined by local policies and availability of equipment. For example:

- By using a probe placed under your nose, your airflow may be measured whilst you sleep.

- A sensor may record snoring volume and body movement whilst you sleep.

- The oxygen level in your blood can be monitored by a probe clipped on to your finger.

- Breathing can be monitored and recorded by the use of special belts placed around the chest and tummy (abdomen).

- A video of you sleeping may be undertaken.

You may be asked to spend a night in hospital for the tests to be done. However, some of the tests may be done in your own home from equipment supplied by the specialist. The information gained from the tests can help a specialist to firmly diagnose or rule out OSAS.

Your doctor will usually check your blood pressure. (OSAS is associated with high blood pressure.) They may also suggest other tests to exclude other causes of your sleepiness. For example, a blood test can check for an underactive thyroid gland.

What is the treatment for obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS)?

General measures

Things that can make a big difference include:

- Losing some weight if you are overweight or obese.

- Not drinking alcohol for 4-6 hours before going to bed.

- Not using sedative drugs.

- Stopping smoking if you are a smoker.

- Sleeping on your side or in a semi-propped position.

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)

This is the most effective treatment for moderate or severe OSAS. It may be used to treat mild OSAS if other treatments are not successful. This treatment involves wearing a mask when you sleep. A quiet electrical pump is connected to the mask to pump room air into your nose at a slight pressure. The slightly increased air pressure keeps the throat open when you are breathing at night and so prevents the blockage of airflow. The improvement with this treatment is often very good, if not dramatic.

If CPAP works (as it does in most cases) then there is an immediate improvement in sleep. Also, there is an improvement in daytime well-being, as daytime sleepiness is abolished the next day. Snoring is also reduced or stopped. The device may be cumbersome to wear at night, but the benefits are usually well worth it. Comments like "I haven't slept as well for years" have been reported from some people after starting treatment with CPAP.

Lifelong treatment is needed. Sometimes you can have problems with throat irritation or dryness or bleeding inside your nose. However, newer CPAP machines tend to have a humidifier fitted which helps to reduce these problems.

Mandibular advancement devices

The mandible is the lower jaw. There are devices that you can wear inside your mouth when you sleep. They work by pulling the mandible forward a little so that your throat may not narrow as much in the night. These devices look a bit like gum shields that sportspeople wear. Although you can buy these devices without a prescription, it is best to have one properly fitted by a dentist if one is recommended. These devices can work well in some cases. They tend to be used in mild OSAS or in people who are unable to tolerate CPAP treatment.

Surgery

Surgery is not often used to treat OSAS in adults. However, sometimes an operation may be helpful to increase the airflow into your airway. For example, if you have large tonsils or adenoids, it may help if these are removed. This is more commonly done in children with OSAS. If you have any nasal blockages, an operation may help to clear the blockage. New operative techniques are being developed for people with OSAS.

Other treatments

If you sleep mostly on your back, then positional therapy can be beneficial. This works to prevent you from sleeping on your back. There are different ways of doing this, including the simple 'tennis ball technique' (a tennis ball is strapped to your back), alarm devices and also using a number of positional pillows to help you change your sleeping position.

Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS) - driving and operating machinery

If you have OSAS and you are a driver, you only need to inform the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) if you have symptoms of excessive daytime sleepiness. For normal car drivers, you will usually be allowed to resume driving after you have had treatment so that you no longer have daytime sleepiness.

Special rules apply if you have an LGV or similar licence.

However, you do not need to stop driving or inform the DVLA if you are being investigated for, or have a diagnosis of, OSAS but do not experience symptoms of daytime sleepiness that are of a severity likely to impair driving.

It is also recommended that you inform the DVLA (but do not cease driving) if you are successfully using CPAP or using a mandibular advancement treatment. If your symptoms are controlled and you have no excessive daytime or awake time sleepiness, then your driving licence will not be affected.

Equally, if you have daytime sleepiness, you should not operate heavy machinery, as this can also be dangerous.

About the author

Dr Louise Newson

BSc (Hons) (Pathology), MB ChB (Hons), MRCP, MRCGP DFFP, FRCGP

Louise qualified from Manchester University in 1994 and is a GP and menopause expert in Solihull, West Midlands. She is an editor for the British Journal of Family Medicine (BJFM). She is an Editor and Reviewer for various e-learning courses and educational modules for the RCGP. Louise has a keen interest on the menopause and HRT and is one of the directors for the Primary Care Women’s Health Forum. She runs a menopause clinic in Solihull and is a member of the International Menopause Society and the British Menopause Society.

Recommended websites

For further reading go to:

- Continuous positive airway pressure – devices (Wikipedia)

- Sleep Apnoea – Wikipedia

- Sleep Apnoea - Cleveland Clinic

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Are you a healthcare practitioner who enjoys patient education, interaction and communication?

If so, we invite you to criticise, contribute to or help improve our content. We find that many practicing doctors who regularly communicate with patients develop novel and often highly effective ways to convey complex medical information in a simplified, accurate and compassionate manner.

MedSquirrel is a shared knowledge, collective intelligence digital platform developed to share medical expertise between doctors and patients. We support collaboration, as opposed to competition, between all members of the healthcare profession and are striving towards the provision of peer reviewed, accurate and simplified medical information to patients. Please share your unique communication style, experience and insights with a wider audience of patients, as well as your colleagues, by contributing to our digital platform.

Your contribution will be credited to you and your name, practice and field of interest will be made visible to the world. (Contact us via the orange feed-back button on the right).