Procedures Explained

Disclaimer:

This website is intended to assist with patient education and should not be used as a diagnostic, treatment or prescription service, forum or platform. Always consult your own healthcare practitioner for a more personalised and detailed opinion

Disclaimer:

This website is intended to assist with patient education and should not be used as a diagnostic, treatment or prescription platform or service. Always refer any concerns or questions about diagnosis, treatment or prescription to your doctor.

Female Sterilisation

We have selected the following expert medical opinion based on its clarity, reliability and accuracy. Credits: Sourced from the website Patient UK, authored by Dr Colin Tidy, Reviewed by Shalini Patni (see below). Please refer to your own medical practitioner for a final perspective, assessment or evaluation.

How is female sterilisation done?

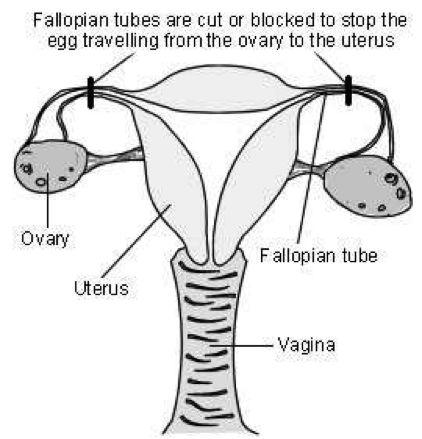

The tubes between the ovary and the womb (the Fallopian tubes) are cut or blocked with rings or clips. This stops the eggs which are released by the ovary from reaching the sperm.

Female reproductive organs

Diagram showing how female sterilisation is performed

The operation is usually done under general anaesthetic but can be done with a local anaesthetic or regional anaesthetic while you are awake. For most women the operation is done with the help of a special telescope called a laparoscope.

The laparoscope is inserted through a very small cut in your tummy (abdomen). It allows the surgeon to see what they are doing. Another small cut is then made to insert an instrument to block the tubes. A number of ways are used to do this. Most often clips or rings are applied to your tubes. The clips or rings provide a block in the tubes and prevent the egg from meeting sperm.

A larger cut may have to be made, and a more traditional operation done, in some women. This is more likely if laparoscopy is too risky, such as if you have had multiple previous operations, or if you are overweight. This is called a mini-laparotomy.

If blocking the Fallopian tubes doesn't work then either part or all of the tubes can be removed. This is called a salpingectomy.

Sterilisation can be performed at the same time as a caesarean section, when a segment of the tube is removed. This is done after the delivery of the baby.

How reliable is female sterilisation?

Around 2-5 women out of 1,000 will become pregnant after laparoscopic sterilisation. As a comparison, when no contraception is used, more than 800 out of 1,000 sexually active women will become pregnant within one year.

After sterilisation, women can (but rarely) become pregnant if the tubes come back together again after being cut. If clips were used to block the tubes, the clips can occasionally work their way off - even when they have been put on correctly.

What are the advantages of female sterilisation?

It is permanent and you (and your partner) don't have to think about contraception again. There are no hormones involved, so you do not have the side-effects of many other types of contraception. It does not affect your periods.

What are the disadvantages of female sterilisation?

Sterilisation is permanent and very difficult to reverse. Some women may regret having the operation in future years, particularly if their circumstances change.

In the rare event that the procedure fails and you become pregnant, you are more likely to have an ectopic pregnancy. This occurs when the pregnancy develops outside of the womb, usually in the Fallopian tube. You would need emergency treatment if this were to happen. If you think you are pregnant after a sterilisation, or have unexplained bleeding or pain in your tummy (abdomen), then see a doctor quickly.

Laparoscopic sterilisation is also not as easy to do or as effective as male sterilisation (vasectomy). There is a small risk from the insertion of the laparoscope which has to be done 'blind' (ie without any image guidance). This means the surgeon cannot see exactly where they are putting the instrument in the tummy to gain access to the tubes. It may at times damage organs like bowel or a blood vessel inside the abdomen. This sounds worrying. However, the surgeon takes many precautions to make the procedure safe and to avoid causing damage to any other organ and, in most cases, this does not happen.

Sterilisation doesn't protect against sexually transmitted infections (STIs) so you may need to use condoms if you think you may be at risk of STI.

As with any operation there is a risk of a wound infection and the slight risk from a general anaesthetic. There may be some tummy discomfort or bloating, or mild discomfort or pain at the site of the cut.

How soon is it effective?

For laparoscopic sterilisation it depends on when you have it done in your menstrual cycle. If it is done whilst you have your period, you will not have produced an egg yet. In this case the procedure is effective immediately.

At any other time in your cycle, you will usually be advised to continue your previous method of contraception until your next period.

(The procedure is only done after checking you are not pregnant. That is, a pregnancy test would be done. If you have had sex without using contraception in the previous three weeks it is not possible to be sure you will not be pregnant. In this case, the operation would be delayed).

Will it reduce my sex drive?

No. Sex may seem more enjoyable, as the worry of pregnancy and contraception is removed.

Some points to consider

Don't consider having the operation unless you and your partner are sure you do not want children, or further children. It is wise not to make the decision at times of crisis or change - for example, after a new baby or termination of pregnancy. Don't make the decision if there are any major problems in your relationship with your partner. It will not solve any sexual problems.

Doctors normally like to be sure that both partners are happy with the decision before doing this permanent procedure. However, it is not a legal requirement to get your partner's permission. If you have any doubts and questions, make sure you discuss these with your doctor or practice nurse.

Have you considered the alternatives?

Female sterilisation is not 100% effective. Other reversible methods of contraception are just as effective, such as the intrauterine system (IUS), contraceptive implants and contraceptive injections. Also, male sterilisation is easier and safer to do and is more effective.

About the author

Dr Colin Tidy

MBBS, MRCGP, MRCP, DCH

Dr Colin Tidy qualified as a doctor in 1983 and he has been writing for Patient since 2004. Dr Tidy has 25 years’ experience as a General Practitioner. He now works as a GP in Oxfordshire, with a special interest in teaching doctors and nurses, as well as medical students. In addition to writing many leaflets and articles for Patient, Dr Tidy has also contributed to medical journals and written a number of educational articles for General Practitioner magazines.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Are you a healthcare practitioner who enjoys patient education, interaction and communication?

If so, we invite you to criticise, contribute to or help improve our content. We find that many practicing doctors who regularly communicate with patients develop novel and often highly effective ways to convey complex medical information in a simplified, accurate and compassionate manner.

MedSquirrel is a shared knowledge, collective intelligence digital platform developed to share medical expertise between doctors and patients. We support collaboration, as opposed to competition, between all members of the healthcare profession and are striving towards the provision of peer reviewed, accurate and simplified medical information to patients. Please share your unique communication style, experience and insights with a wider audience of patients, as well as your colleagues, by contributing to our digital platform.

Your contribution will be credited to you and your name, practice and field of interest will be made visible to the world. (Contact us via the orange feed-back button on the right).