Procedures Explained

Disclaimer:

This website is intended to assist with patient education and should not be used as a diagnostic, treatment or prescription service, forum or platform. Always consult your own healthcare practitioner for a more personalised and detailed opinion

Disclaimer:

This website is intended to assist with patient education and should not be used as a diagnostic, treatment or prescription platform or service. Always refer any concerns or questions about diagnosis, treatment or prescription to your doctor.

Urodynamic Tests

Also known as "Urinary Incontinence Tests"

We have selected the following expert medical opinion based on its clarity, reliability and accuracy. Credits: Sourced from the website Patient UK, authored by Dr Louise Newson, reviewed by Dr Adrian Bonsall (see below). Please refer to your own medical practitioner for a final perspective, assessment or evaluation.

Overview

Urodynamic tests check the function of your bladder and help to investigate the cause of any urinary incontinence you may have.

Note: The information below is a general guide only. The arrangements, and the way tests are performed, may vary between different hospitals. Always follow the instructions given by your doctor or local hospital.

What are urodynamic tests?

Urodynamic tests help doctors assess the function of your bladder and the tube from your bladder that passes out urine (your bladder outflow tract, or urethra). They are often done to investigate urinary incontinence.

During the tests, your bladder is filled and then emptied while pressure readings are taken from your bladder and your tummy (abdomen). The idea is to replicate your symptoms, then examine them and determine their cause.

What are urodynamic tests used for?

Urodynamic tests are used to help diagnose:

- Stress urinary incontinence

- Urge urinary incontinence

- Mixed urinary incontinence (stress and urge urinary incontinence)

They may also be helpful in investigating other causes of incontinence. Urodynamic tests are particularly important if surgery is being considered for the problem, to make sure the correct operation is performed.

Understanding urine and the bladder

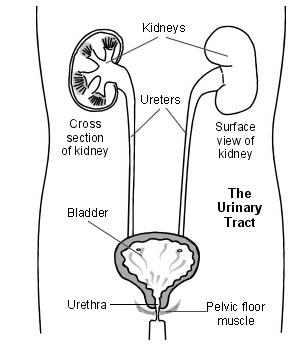

The kidneys make urine all the time. A trickle of urine is constantly passing to the bladder down the tubes from the kidneys to the bladder (the ureters). You make different amounts of urine depending on how much you drink, eat and sweat.

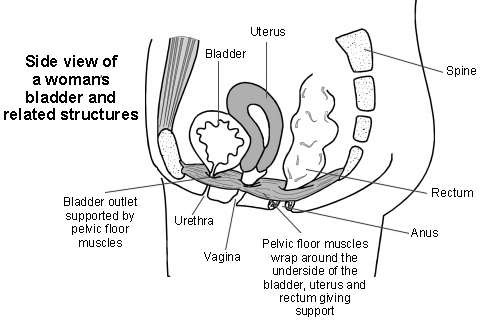

The bladder is made of muscle and stores the urine. It expands like a balloon as it fills with urine. The outlet for urine (the urethra) is normally kept closed. This is helped by the muscles beneath the bladder that sweep around the urethra (the pelvic floor muscles).

When a certain amount of urine is in the bladder, you become aware that the bladder is getting full. When you go to the toilet to pass urine, the bladder muscle squeezes (contracts), and the urethra and pelvic floor muscles relax.

Complex nerve messages are sent between the brain, the bladder and the pelvic floor muscles. These tell you how full your bladder is and which muscles are right to contract or relax at the correct time.

Understanding incontinence

Urodynamic tests can help doctors assess which type of incontinence you have. The treatment that you receive will differ depending on the type of incontinence you have.

There are a number of different causes of incontinence including the following:

- Stress incontinence is the most common type: It occurs when the pressure in the bladder becomes too great for the bladder outlet to withstand. It usually occurs because your pelvic floor muscles which support your bladder outlet are weakened. Urine tends to leak most when you cough or laugh, or when you exercise (such as when you jump or run). In these situations there is a sudden extra pressure (stress) inside your tummy (abdomen) and on your bladder.

- Urge incontinence (unstable or overactive bladder) is the second most common cause: In this condition you develop an urgent desire to pass urine. Sometimes urine leaks before you have time to get to the toilet. The bladder muscle contracts too early and the normal control is reduced.

- Mixed incontinence: Some people have a combination of stress and urge incontinence.

How do urodynamic tests work?

The first part of the tests checks how much urine leaves your bladder over a certain length of time. This is called the flow rate. A special toilet records the flow of your urine. A computer then checks for any abnormalities in flow rate.

A decreased flow rate can indicate problems with bladder emptying. For example, this could be an obstruction to bladder drainage or underactivity of your bladder muscle.

The second part of the tests is called filling cystometry. For this test, thin tubes called catheters are inserted into your bladder and your back passage (rectum) or your vagina. These can measure the pressure in your bladder and tummy (abdomen) as your bladder fills with fluid. Using these measurements, doctors compare the different pressure readings.

If urine leaks with no change in pressure in your bladder muscle, you may have stress incontinence. Leaking is brought on (provoked) by an increase in pressure inside your abdomen - for example, when coughing.

If involuntary bladder muscle activity causes an increase of pressure in your bladder and leads to leaking, you may have urge incontinence.

What happens during urodynamic testing?

Testing is done in a room in the X-ray department.

For the first part of the test, you will need to empty your bladder into a special toilet called a flowmeter. This measures how much urine you pass and the flow of the urine. You will usually be left alone in the room whilst you are doing this. This is why you need to come to the test with a full bladder.

Once you have been to the toilet you will usually have an ultrasound test performed to see how empty your bladder is. This test is done by having some gel on the skin over your bladder and then an ultrasound probe being moved over this area.

The next part of the test measures the way your bladder works as it fills up. You will be asked to lie down on a special bed. Two very thin tubes (catheters) are put into your bladder, by inserting them into the tube from your bladder that passes out urine (your urethra). You may find this a little uncomfortable. One is to fill up your bladder and the other is to measure the pressure in your bladder. Another catheter is put into your vagina or back passage (rectum). This allows the pressure inside your bladder to be compared with the pressure outside your bladder.

Once the catheters are in the correct position, fluid runs into your bladder at a controlled rate. This slowly fills your bladder whilst recordings are made. The doctor or nurse performing the test will ask you questions - for example, how your bladder feels and when it feels full.

Once your bladder is full, the bed will move and stand you upright. You may be asked to cough and some X-rays of your bladder are taken.

If you leak urine when you cough, try not to feel embarrassed. If you leak at home when you cough, it is best for the test operator to see you leak during the test. It is important to remember that it is helpful to see how your bladder behaves on a day-to-day basis to make sure that the correct treatment is provided.

You will then be asked to empty your bladder into the special toilet again at the end of the test, with the catheters still in place.

What should I do to prepare for a urodynamic test?

If you are taking any medication for your bladder then it is likely that you will be asked to stop this for a week before this test.

Your hospital may ask you to arrive for your test with a comfortably full bladder. If this is difficult, some hospitals may ask you to arrive a little early so that you can have a drink to fill your bladder.

The test usually takes around 2-3 hours.

What can I expect after a urodynamic test?

After the tests some people feel a slight stinging or burning sensation when they pass urine. If you drink plenty of fluids these symptoms should quickly settle. If discomfort lasts more than 24 hours, you should take a sample of your urine to your GP for testing because it may be a sign of infection.

Some people find a small amount of blood in their urine when they go to the toilet. If this lasts more than 24 hours, you should also see your GP because it may be a sign of infection.

After having urodynamic tests there is a small possibility that you may develop a urinary tract infection. This is caused by putting the very thin tubes (catheters) into your bladder during the test.

To help reduce the likelihood of developing an infection after the test, your hospital may advise you to:

- Drink extra fluids for 48 hours after the test. This will help you to 'flush' your system through. Aim to drink about two and a half litres a day for the 48 hours after the test (9-10 cups of fluid).

- Cut down on your tea and coffee intake for 48 hours after the test. This will reduce bladder irritation until your bladder returns to normal. Drink water, herbal and fruit teas, juices and squash.

- When you go to the toilet to pass urine, take a bit longer to make sure that your bladder is fully empty. When you have finished passing urine, wait for a couple of seconds and then try again.

Are there any side-effects or complications from a urodynamic test?

Some urodynamic tests involve using X-rays. X-rays should not be used on pregnant women so let your doctor know before the test if you are, or think you could be, pregnant.

Most people have urodynamic tests without experiencing any problems. As mentioned above, there is a small chance of developing a urinary tract infection.

Contact your GP if you develop any of the following symptoms:

- A stronger than usual urge to pass urine.

- Your urine smells, is cloudy or has blood in it.

- You want to pass urine more often during the day and night.

- A burning or stinging sensation when you pass urine and feel that you are only passing small amounts at a time.

- Lower backache or pain in your kidneys.

- If you feel hot and develop a high temperature.

About the author

Dr Louise Newson

BSc (Hons) (Pathology), MB ChB (Hons), MRCP, MRCGP DFFP, FRCGP

Louise qualified from Manchester University in 1994 and is a GP and menopause expert in Solihull, West Midlands. She is an editor for the British Journal of Family Medicine (BJFM). She is an Editor and Reviewer for various e-learning courses and educational modules for the RCGP. Louise has a keen interest on the menopause and HRT and is one of the directors for the Primary Care Women’s Health Forum. She runs a menopause clinic in Solihull and is a member of the International Menopause Society and the British Menopause Society.

Dr Adrian Bonsall

MA (Chemistry), MB BS (Hons), DCH

Qualified in 1997. Since 2000 has worked in tertiary care paediatric hospitals and adult critical care in Australia, based in Sydney specialising in paediatric emergency medicine with particular interests in toxicology, trauma and paediatric resuscitation. Also works for the neonatal & paediatric retrieval service in NSW.

- 20 years as an author & peer-reviewer of medical articles.

- Co-author of a number of Australian paediatric acute care guidelines.

- Contributing author to The Textbook of Paediatric Emergency Medicine (3rd Ed. Elsevier)

- Advance Paediatric Life Support instructor delivering courses across Australia & Fiji since 2008.

- University NSW medical student tutor.

- Professional computer programmer producing non-medical and medical application software for over 30 years.

Recommeded websites

For further reading go to:

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Are you a healthcare practitioner who enjoys patient education, interaction and communication?

If so, we invite you to criticise, contribute to or help improve our content. We find that many practicing doctors who regularly communicate with patients develop novel and often highly effective ways to convey complex medical information in a simplified, accurate and compassionate manner.

MedSquirrel is a shared knowledge, collective intelligence digital platform developed to share medical expertise between doctors and patients. We support collaboration, as opposed to competition, between all members of the healthcare profession and are striving towards the provision of peer reviewed, accurate and simplified medical information to patients. Please share your unique communication style, experience and insights with a wider audience of patients, as well as your colleagues, by contributing to our digital platform.

Your contribution will be credited to you and your name, practice and field of interest will be made visible to the world. (Contact us via the orange feed-back button on the right).